Trump’s Twitter Ban Is Good for Free Speech

President Biden’s inauguration ended the presidency of Donald J. Trump, but Trump’s influence arguably slipped away once he lost access to mainstream social media platforms. His permanent ban from Twitter, once his primary method of attracting voters and occasionally firing government officials, emphasized the point: the voice of the president, though not eliminated, was permanently changed in the aftermath of the Capitol insurrection. Many of Trump’s detractors celebrated his suspension, but others decried it as a violation of his constitutionally-guaranteed freedom of speech. Even Twitter’s Jack Dorsey worried about the “dangerous” precedent the ban set. Some have been quick to point out that the First Amendment regulates government censorship, not private corporations, but many Americans are concerned about more than the ban’s constitutional implications. Freedom of speech is a cultural value that transcends the law and has become a durable hallmark of modern conservative discourse. Trump’s suspension raises a number of pressing questions about this cultural notion of free speech, and whether tech giants such as Twitter have too much power to regulate it. Despite these questions, I would argue that Trump’s Twitter ban does not foreshadow the end of free speech in the United States. The ban is, in fact, beneficial—perhaps even necessary—for the preservation of free speech.

Donald Trump swiftly raised the issue of freedom of speech after his Twitter ban. When Twitter suspended his infamous @realDonaldTrump account, Trump relocated to the official @POTUS account, using it to suggest that “Twitter is not about FREE SPEECH,” but is instead just another corporation creating a “Radical Left platform where some of the most vicious people in the world are allowed to speak freely.” Nevertheless, Trump’s access to this account and to any other Twitter account was quickly restricted.

Trump’s tweets alleging favoritism of liberal causes by major media and tech companies are hardly new, and the notion is hardly his creation. Indeed, claims of rebellion against liberal censorship have been a hallmark of modern populist conservatism for many years. As a kid, I heard Bill O’Reilly and Sean Hannity on my parents’ TV every day spouting off complaints about the so-called War on Christmas and insisting that textbooks were being rewritten to delegitimize Judaism and Christianity. Trump’s complaints are hardly original.

I do not mean to say that these claims of censorship are baseless. I have several close friends and family members who claim to have had their own voice silenced. On the other hand, I am inclined to think that platforms that refuse to silence voices such as Donald Trump until something as egregious as an attempted insurrection occurs are not eager to censor conservative voices, let alone populist ones such as his. However, I do not wish to address these claims of censorship. My argument defending Trump’s ban is more about the fundamental nature of the freedom of speech.

Freedom of speech is not simply the right to speak, publish, gather or worship without undue government interference, as promised in the First Amendment. Free speech is a much larger ethical and cultural force. Freedom of speech seems to be widely understood as the right to do the activities described or implied in the First Amendment not only without government interference, but also without fear of social stigmatization, exclusion or other undue or disproportionate reprimands from others, especially those perceived to hold power. The reason some see the so-called War on Christmas as a free speech issue is because those involved in the “war” see a powerful liberal culture as compelling them to say “happy holidays” rather than “Merry Christmas.” Whether this concern is exaggerated or unnecessary is, of course, worth asking, but it nonetheless serves as a valuable illustration of the cultural notion of free speech. Freedom of speech is not merely a legal or human right, but an assertion of identity and values against a perceived wave of cultural repression or homogenization. Freedom of speech is framed as a virtuous act of rebellion in defense of traditional, objective values, especially in conservative circles.

Of course, freedom of speech also has an uglier cultural role, especially online. Parler, a self-proclaimed free speech social media platform, became a haven for white supremacist rhetoric and calls for violence which precipitated in the insurrection at the Capitol. Its recent removal from major app stores has certainly raised legitimate concerns about the substantial power tech giants wield to control speech. These concerns, though, do not lessen the danger of the abuse of freedom of speech that took place on Parler.

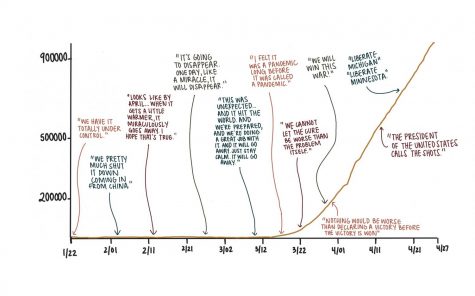

Trump’s Twitter embodied the difficulties of freedom of speech. Trump’s tweets frequently pointed to freedom of speech as a cultural virtue, but his spread of misinformation about the 2020 election was a persistent and dangerous abuse of that freedom. The fact that multiple members of Congress and a broad swath of Americans repeat or believe that misinformation only makes it a more dangerous abuse and does not grant it any legitimacy. Popularity does not make speech any truer; in fact, it makes lies more dangerous and damages our trust in truth. As Twitter noted in their blog post announcing the ban, it was not simply the content of his tweets that prompted his suspension, but also “the context around them — specifically how they are being received and interpreted on and off Twitter.” That his tweets were being interpreted and reused as endorsements of violence made them unacceptably dangerous.

Of course, this raises a point that may make Trump’s ban detrimental to freedom of speech. Should we be censored simply because someone else takes our speech and uses it to further another hateful, violent cause? Should we suffer for another person’s abuses?

In general, no, we should not. Misunderstandings and misrepresentations of speech, whether digital, spoken or printed, are by definition inaccurate and do not necessarily reflect the character or intentions of the original speaker. Of course, a speaker may intentionally speak ambiguously to encourage conflicting interpretations while escaping responsibility for those who use the speech for evil ends. Trump’s “stand back and stand by” remark about the white supremacist Proud Boys is arguably an example of such deliberately ambiguous speech. Yet while Trump was widely and rightfully criticized for that remark, he did not suffer any censorship for it. It would be, in the end, the Proud Boys who would be responsible for using that line as a slogan for their violent ends.

When that sort of ambiguous speech is repeated, however, the answer to the above questions differs slightly. When it becomes clear that a person’s speech about certain sensitive topics—such as the legitimacy of the 2020 election—will be inevitably read as an endorsement of something as violent as insurrection, that person’s choice to continue that speech is a sign of either irresponsibility, ignorance or willful complicity in that violence. Ignorance is the only of those three cases that is excusable, though given that Trump had a penchant to read and retweet his followers’ replies, this defense may not be so viable.

However, it is immensely difficult for a person to avoid having their speech used for evil ends, especially when that person is as powerful and influential as Trump is. Blaming Trump for some of his followers using his tweets to rationalize the Capitol riot might be like blaming J.D. Salinger because Mark David Chapman used The Catcher in the Rye to rationalize killing John Lennon. Perhaps the insurrectionists at the Capitol would have tried to use his tweets for their violent ends even if he called for their arrest and prosecution and agreed to attend Biden’s inauguration. Trump may deserve the benefit of the doubt in this case, if only to preserve the integrity of the freedom of speech.

There are a few factors that undermine this defense. The first is that Trump’s Twitter ban was not prosecution. Trump is not totally censored. Until January 20, he had a press briefing room, C-SPAN and a large flock of journalists and followers who would immediately share any video he released on every social media platform from which Trump has been banned. He still had presidential authority. Unless Congress successfully convicts Trump for inciting insurrection, the most he suffered was losing one of several outlets he has for speech. No matter what happens, he will likely have a reduced but still notable platform for a long time to come. On balance, Twitter, Facebook and Instagram have not silenced Trump, but simply reduced the damage he caused on the platforms they own and manage.

The second factor is the nature of social media itself. I would argue that social media exists at a strange intersection of spoken and written speech. Many of us use social media to express our thoughts in real time without much editorial concern, but our tweets and posts become permanent; our social media posts take on, to some extent, a life of their own. As soon as someone screenshots one of our posts, it lives on beyond our control. Trump’s most controversial tweets survive even as his Twitter drifts into nothingness. In fact, we hardly have total control over our posts in the first place, even if nobody screenshots or otherwise saves it; our posts are hosted and managed by private corporations. We sign at least partial control of these specific speech acts over to those who manage these platforms. Freedom of speech is not freedom of dissemination, especially when we willfully yield the process of dissemination to another private entity by using their platform. Social media platforms’ user agreements could perhaps stand to give users more leeway over how moderators treat their posts, but platform moderators need to exercise some sort of control over how these posts spread and are used by others.

Not only are the means of suspending Trump’s account ethical, but so are its ends. Freedom of speech does entail permitting speech that is false or even somewhat dangerous, but only as an unintended effect of preserving the greater good that is free and open discourse among people of various opinions and walks of life. Freedom of speech, for all its problems, is a necessary component of maintaining democracy and the common good. In fact, it is those aims that make freedom of speech meaningful and necessary. Trump’s suspension from Twitter was based on the use of his tweets to endorse violence and misinformation campaigns in the wake of an attempted insurrection that took place two days earlier. Any reasonable person would acknowledge that the insurrection was harmful to democracy and to the common good. It threatened the institutions established to protect our individual freedoms. It was not responsible or reasonable dissent; it was a deadly act of vandalism threatening the fabric of our country. Trump’s tweets, over which Twitter has certain controls, were exacerbating that harm. Suspending Trump was Twitter’s only sufficient means of preventing further, perhaps irreparable damage to democracy and to the common good, barring a sudden change of heart from Trump. Furthermore, when the concept of freedom of speech is abused to harmful ends, just as Trump and some of his followers do, it loses its meaning. It becomes empty permissiveness to the detriment of all. For conservatives invoking freedom of speech to protect their traditional values, it seems that efforts to prevent this degradation of freedom of speech should be all the more necessary.

Trump’s suspension in the wake of the Capitol riot raises some difficult questions. Who are Twitter, Facebook and Instagram that they can determine what sort of speech is in the interest of the common good? Where is the balance between the good of free speech and the good of preventing harm to democracy? Is it good for our democracy to yield so much control over our communications to tech giants? Raising these questions, however, does not change the fact that Trump’s Twitter ban was rational, balanced and necessary. The broader societal role of social media companies such as Twitter is still hard to define, as is the extent to which they should have power over our communications. Whatever power they do have, though, they exercised justly in this case.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Saint Louis University. Your contribution will help us cover our annual website hosting costs.

S • Feb 19, 2021 at 8:57 am

Your argument is too one sided. The problem is, it isn’t just Trump that had been spreading misinformation on social media platforms. You and I can, other politicians can, my grandma can…etc. The fact of the matter is, Twitter is choosing who they ban. When politicians incited violence over the summer, instead of condemning it, by these standards shouldn’t they have been banned? Every time a politician says a misleading statement shouldn’t they be banned – they are misleading the public and contributing to the hatred and anger.