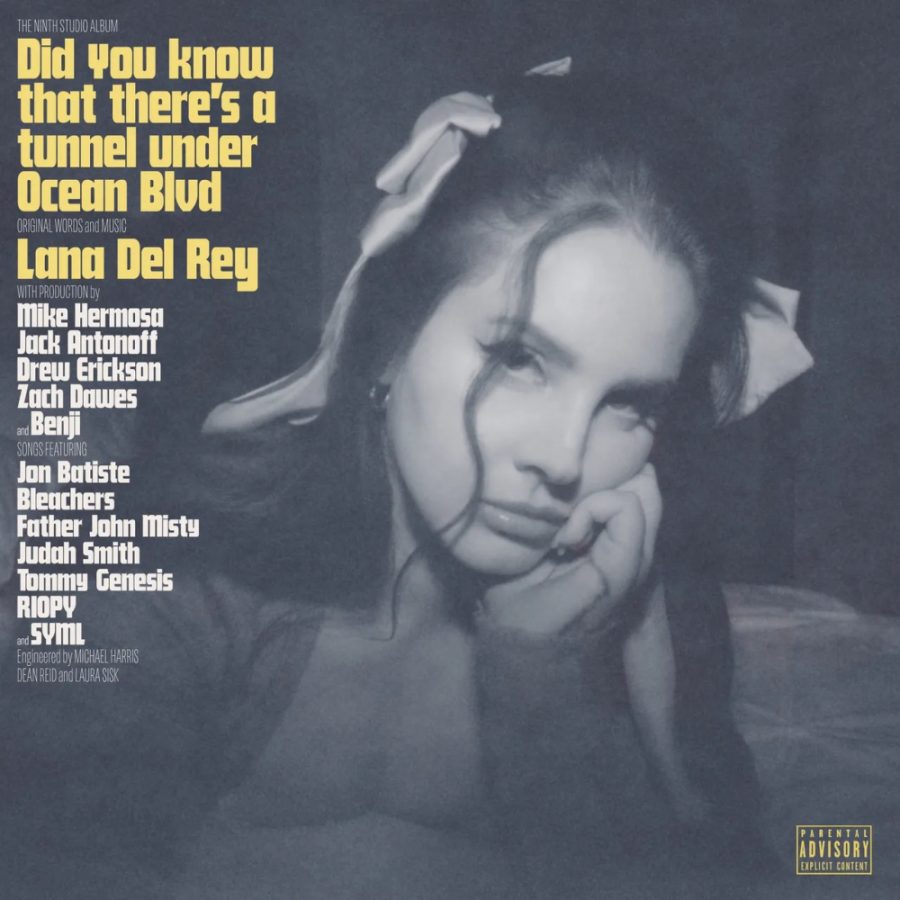

There’s A Tunnel Under Ocean Boulevard: Lana Del Rey’s Clearest Mirror

There’s a tunnel under Ocean Boulevard. It was built in Long Beach, California, in 1927 to provide a safe passage to the beach for pedestrians and was closed to the public in 1967. As Lana Del Rey compares herself to this tunnel on the title track of her ninth album, she asks, with a melancholic certainty, when her “handmade beauty” will be “sealed up by two man-made walls.” “When’s it gonna be my turn?” she sings, asking not if, but when. Still, in the same way her poetry often comes across as an omen, someone who sees what you’ll learn from a heartbreak before the heartbreak comes, she already knows the answer.

On her ninth album, she has accepted that her beauty is soon to be like the mosaic ceilings and hand painted tiles in the titular tunnel. No longer the siren she was at 20, she is closed off to those who don’t wish to walk through her to get to the beauty on the other side. With her youth and relevancy under attack, her response is the opposite of a battle cry. Instead, she greets this form of death without a plea to survive, but a chuckle, a laugh in the face of critics who expect her to keep holding onto her cultural grasp and vibrance. On “A&W,” she asks “do you really think I give a damn what I do after years of just hearing them talking?” This time, everyone knows the answer.

As if she has the tunnel to herself, her lyrics roll off her tongue like the most personal journal entries, taking on a Mark Kozelek-esc approach to her ruminations that often favors scattered details over her traditional poetic one-liners. She places ramblings over fluffy beds of piano and strings, and sometimes trap beats, on “A&W,” “Peppers,” “Fishtail”, and “Taco Truck & VB,” and allows the audience to connect the emotive dots between narrative details.

The full 77 minutes features less instrumental variation than lyrical prowess, which she has a lot of. There are points where the instrumentation, washed out in reverb, sounds itself like it was recorded in a tunnel. The atmosphere rarely fades, but slowly grows stale, and the listener is asked to dig through the surface monotony to take Lana’s messages to heart. Although there is much to be said, by the time “Let The Light In” starts, the simple sounds of an acoustic guitar and Father John Misty’s voice is a much needed break of habit.

Still, it is the clearest mirror Lana has held in front of her, whether it takes the form of the stream-of-consciousness “Fingertips,” or the self-destructive, multi-phased “A&W.” Here, nothing is off the table. “Taco Truck & VB,” which closes the record on a sample of “Norman Fucking Rockwell” standout “Venice Bitch,” opens with a request for someone to pass her vape. “Margaret,” a collaboration with Jack Antonof’s, who produced much of the record, Bleachers, ends with an invitation to a party on December 18th. “If you want some basic bitch, go to the Beverly Center and find her,” she sings on “Sweet.” Her calm cracks on “Candy Necklace,” singing eerily about her recklessness with a man she is infatuated with. The six and a half minute “Kintsugi,” which has one of the most stunning refrains on the project, is the most verbose Lana song ever, and it’s strikingly revealing..

Though the ramblings yield many highs, the best song is at the beginning. “The Grants,” named after her family, contains one of her strongest melodies ever, and the sentimental refrain and familial references make it her first undeniable tear-jerker. She uses it to remind listeners that all the heartbreak and happiness thread throughout the 77 minute record are part of the same “beautiful life.”

And that’s the essential message of the album: all of the stunning and all the forgettable, all the tasteful and tacky, all the irreverent and all the dead-serious, is part of the same Lana. She is letting loose for herself and the fans who won’t forget her when her beauty fades. Every moment of self-indulgence adds to the reflection this record creates, making the collection of songs feel like a character portrait. As she observes on “Kintsugi,” the charm is often in its cracks, which are quickly recognized but easily forgiven.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Saint Louis University.