As college students, we have not taken the initiative to learn about the city we reside in, and Saint Louis University has failed to educate us on it. The boastful city of St. Louis is the pinnacle of beauty and waste. Filled with abandoned homes, the city neglects its potential by letting them rot depending on the economic status of each block. St. Louis is choosy. Street by street you feel the difference, and this can be easily seen just around SLU’s campus as well.

Sometimes, students may not take the initiative to learn about the city that they live in, and if they do, hearsay is the most common way they are informed. As we move through our lives we have the ability to leave an impact wherever we go, and a place like St. Louis is desperately waiting to be understood.

One of the more popular areas in the city, the Delmar Loop, attracts many St. Louis residents, particularly Washington University and SLU students. The street blossoms with color and attractions. As you walk with friends, you will notice a variety of shops such as record stores, tattoo parlors, art shops, clothing stores and other miscellaneous things. In my experience, Delmar flaunts with character and music.

As scenic and boastful as the street can be, it is also full of local restaurants waiting to be explored. It spans six blocks of dazzling neon signs and is home to 46 multinational restaurants, and of course, the loop trolley.

The Loop has been nationally recognized for many of its goods: the street, food, music, neon signs and a 3,000-pound moon. In 2007, according to exploreSt.Louis, it was one of the first streets to be recognized by the American Planning Association as “One of the 10 Great Streets in America.” The street was made to be explored and has become a marker of pride in St. Louis.

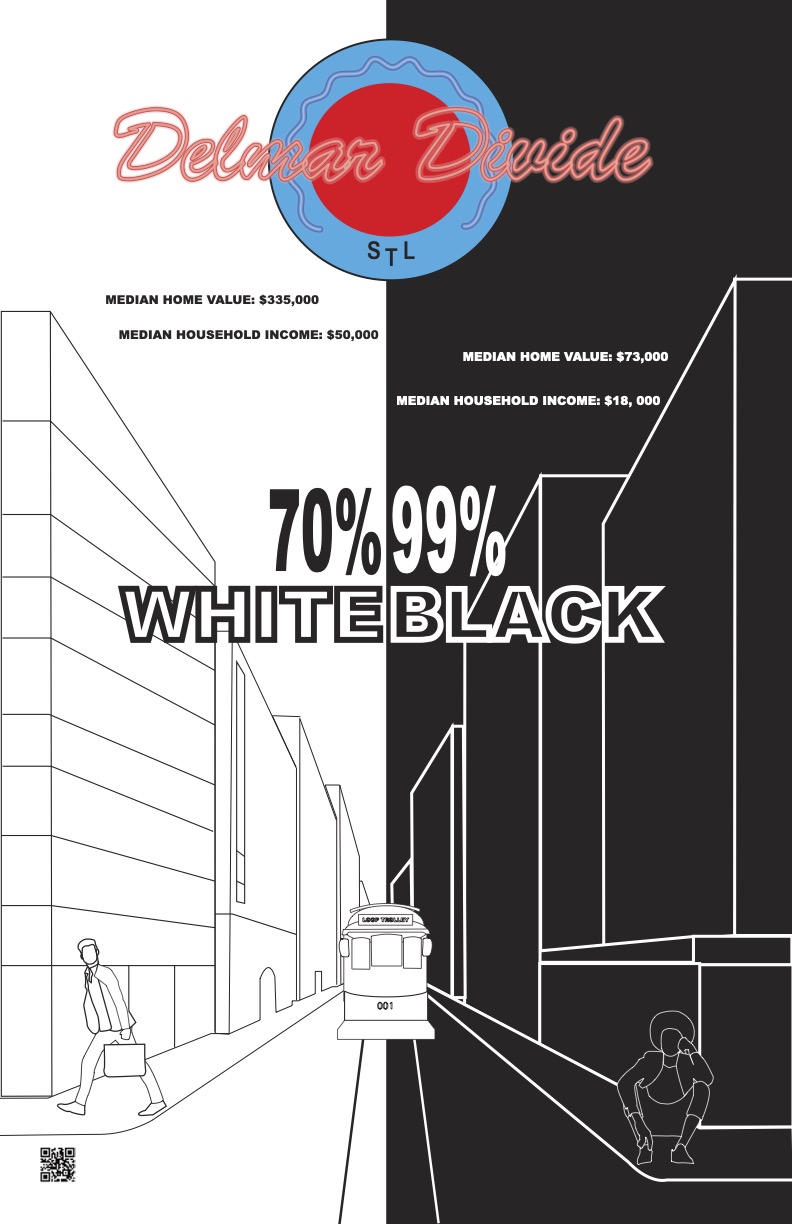

Though, there are some things you will not see on the websites gushing about the greatness of the Delmar Loop, and that is that its bright neon signs pull the light away from the bleak and stark reality that it signifies the greatest racial divide in the United States.

Photo by Robert Cohen

The Delmar Divide “refers to Delmar Boulevard as a socioeconomic and racial dividing line.” There is a significant difference between the blocks in the immediate north and south. In the south blocks, there are “tudor homes, wine bars, a racquet club, a furniture store selling sofas for $6,000.” In these blocks, the neighborhood area is about 70% white, and a median home value of $335,000 while the median household income is $50,000. This area south of Delmar, is built up with historical homes, gates and properties. It booms with business and money running through its streets. Once you look north though, things are strikingly different.

North of Delmar lies a series of abandoned homes. You will see fewer furniture and grocery stores and many more liquor stores. There is little economic opportunity and extremely low incomes. This area north of Delmar is 98% Black with a median household income of $18,000, and median home value of $73,000.

Jessica Carter, a 21-year-old who now lives in Shaw, said that when she used to live in north St. Louis, it was a dump.

“I had mice and roaches because they were dumping trash behind my apartment building, so I felt like that neighborhood was used as a trash heap,” Carter said.

She also explained how living in the north meant there were limited resources and stores such as Family Dollar and Walmart were about 20 to 25 minutes away.

“There weren’t many accessible shops within that area,” Carter said. “I would say there were two corner stores that got shot up every couple weeks, so then it would be closed down after. The stores only really had canned food and ramen. There was nothing really convenient in that area, minus the fact that a lot of the buildings over there were falling apart.”

These two alternate realities rarely connect, at least south to north. It is uncommon for someone from the south neighborhoods to go to the north, whereas, residents from the north often come down to the south neighborhoods for food and shops. Whenever people from the north do venture down, problems often arise.

Black residents from the north of St. Louis have often reported that they feel targeted when they venture down south. These experiences include, but are not limited to, racial profiling and prejudice.

Nile Winfield, a senior at McKinley CL High School, used to live in the Penrose neighborhood located north of Delmar. For him and many others, the street of Delmar is the line.

“When I go to work everyday I pass Delmar, and I instantly see the difference,” Winfield said. “I have never seen a white man in his neighborhood carrying a gun in his pocket, or even just things like trash all over the street. You can just tell there’s more opportunity when you cross that line.”

Winfield explained that in his time north of Delmar, he experienced violence and a lack of resources.

“I have had family members murdered or shot, all the typical hood stuff,” Winfield said. “I remember being shot at as a baby, not aiming for me but I remember the crossfire.”

Photo by Stephanie S. Cordle for The New York Times

Alongside gun violence, racial profiling is an eminent issue across the country, but in St. Louis, Delmar Blvd acts as modern-day segregation.

According to the Washington Post, a student saw “two Black men who were ‘dressed a little raggedy’ walking down the street,” and shortly after, “a police officer stopped them, patted them down and told them to sit on the curb.” Later on, the men were told to “head north, toward Delmar Boulevard.”

This scenario is not new to residents who live south of Delmar, and as a resident of St. Louis myself, I can also affirm that I have seen racial profiling such as this in these areas. I have experienced such profiling alongside my Black friends and it makes me extremely frustrated. How have we come so far but gained so little? How do we turn a blind eye to the struggles in our community, even if we are just a part of the SLU bubble? I think it is time to start asking real questions about how St. Louis city is majority Black, but SLU’s demographics are 55.7% white and 7.1% Black.

These forms of prejudice only further push the areas apart and if as SLU students we continue to not acknowledge it, we too become part of the problem, and in many ways – we already are.

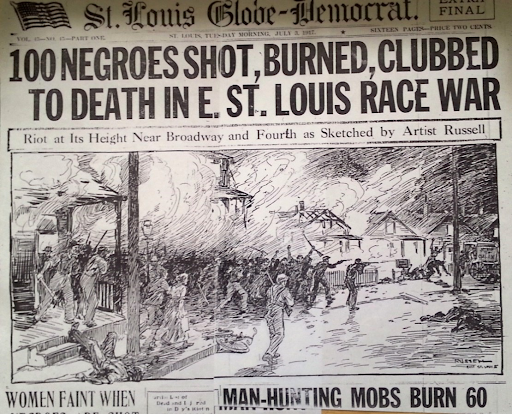

How did this happen?

During the Jim Crow era, there was an ordinance that stated that if “75% of the residents of a neighborhood were of a certain race, no one from a different race was allowed to move into the neighborhood,” (Lion of the Valley). This ordinance was quickly challenged by the NAACP and ruled out in court, but was quickly followed with another restrictive practice called racial covenants.

Racial covenants are clauses that were inserted into property deeds to prevent people who were not white from buying or occupying land. These racial covenants were ruled unconstitutional in 1948, but can still be found in property deeds today. While these practices are illegal it is still practiced.

Ordinances such as these were the starting point for the divide we see today. Places such as The Ville and Mill Creek Valley were known to be African American neighborhoods, but in 1959, they began to gentrify the area for Saint Louis University, Highway 40, Grand Towers and LaClede Town. In order for redevelopment to occur, they displaced all of the residents in that community, who were mostly Black. These residents were moved north of Delmar.

Saint Louis University and Washington University conducted a research study on how socioeconomic issues affect one’s health, and in this study, they found that barriers such as poverty and unemployment affect African Americans in St. Louis at a much higher rate. The research states that “St. Louis is still confronting the legacy of past policies and practices. It remains one of the most segregated metropolitan areas in the U.S.”

As students, it is important to be aware of how St. Louis is built and how it affects opportunities for others. I often hear from students that they thought SLU would be more diverse since St. Louis is one of the few cities that has more Black people than white. Around SLU, we are surrounded by the areas south of Delmar, and SLU is often referred to as a bubble. This is because SLU hides the harshness of racial segregation that still exists in St. Louis. We do not see the diversity it markets because the Black communities have been pushed out of university areas and the financially growing communities. Money needs to be put into these communities as well, and in a way that people can still afford to live there. If we want to talk about progress and inclusivity, this is the deep rooted issue we need to address.

Anonymous • Aug 6, 2024 at 9:55 pm

I enjoyed this artlicle! One thought I had is that I think there should be more of a drive to not make the north of Delmar seem like a violent and dangerous place. I grew up in The Ville and I still live here. The quotes are correct. It is a food desert, there are gun shots, it is a bit of a dump, there is certainly racial profiling, and a majority of the people that live here have a low income. I am not taking away from anyone’s experience. I speak from my own experience when I say that, a lot of us that live here live like every one else. Not all of us carry guns. People that do not live on the north side think it is too dangerous to come around and that they will die as soon as they enter. The North of Delmar is the reason some SLU students feel SLU/St. Louis is unsafe. This is not all true. I’ve lived here all of my life and have never had an issue. I think that stereotypes about people that live in these areas of St.Louis, specifically predominantly black areas, should also be of discussion. Thank you for the article and the knowledge you shared!