Since the 1950s, the idea of the blonde bombshell has become an inescapable element of American pop culture.

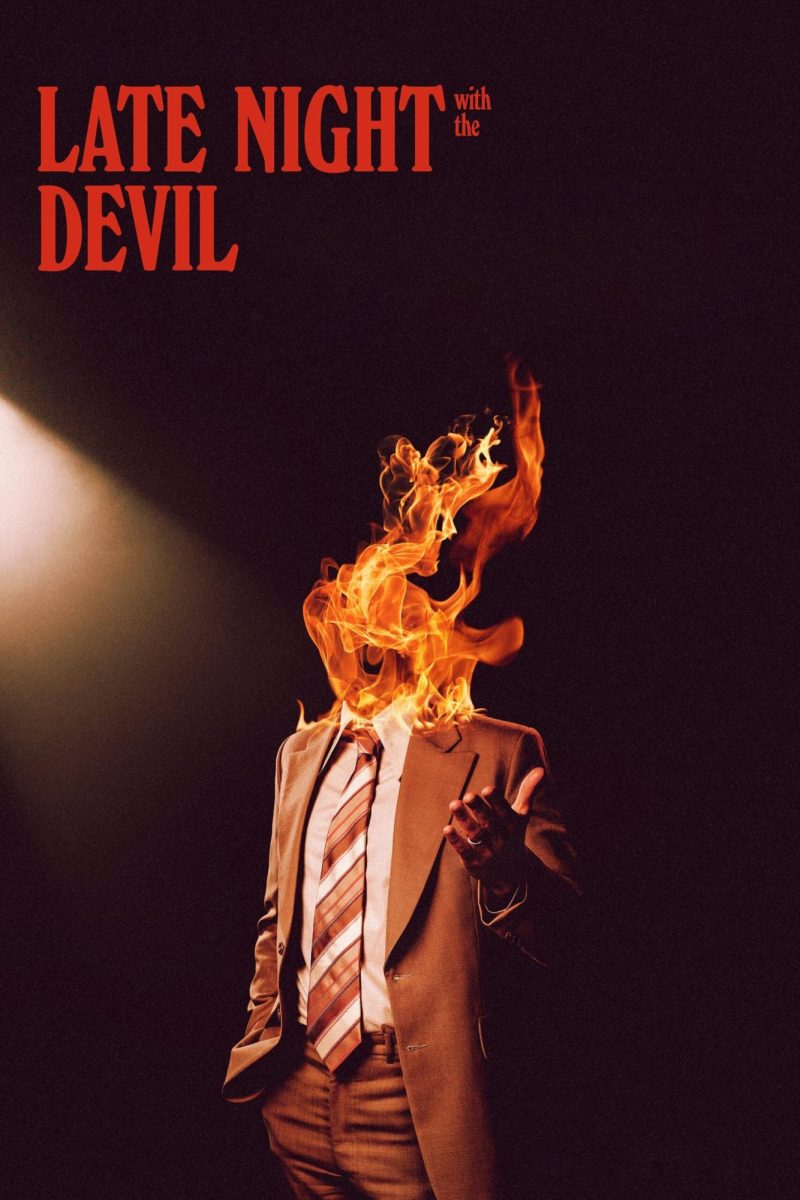

“Beauty and the Blonde,” a new exhibit at the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum on the Washington University campus near the Skinker MertoLink Station, examines the image of the blonde from early advertising and entertainment media to the art world’s often avant-garde response. This past week, The Tivoli accompanied this exhibit with the airing of three classic films featuring iconic blondes.

The first film in the series, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, is arguably the most important in its contribution to elevating the glamorous blonde, here portrayed by pop-culture legend Marilyn Monroe.

The story of two showgirl-best friends is beyond hokey and far over the top by today’s standards. Their scheme to acquire husbands and wealth achieves a type of complication matched only by 007’s greatest villains’ machinations regarding the former. While many fans of this variety of vaudeville-inspired humor and dance can be entertained by the film, others will view it as an archaeologist examines a relic.

As Gentlemen is to pop culture, Vertigo, the second film, is to film culture. The Alfred Hitchcock thriller is rated the ninth best film of all time by The American Film Institute. Ideas of identity, central to the “Beauty and the Blonde” exhibit, are found at the heart of this detective thriller’s plot.

Jimmy Stewart, the mega-star of Hollywood’s golden age in the mid-1900s, stars as an ex-cop hired to follow an old friend’s wife-a blonde, of course-who claims to be possessed by another’s spirit.

Following her suicide, Stewart’s character encounters a woman who bears a striking resemblance to his late wife. To describe the plot any further would be unfair to those who have not had the pleasure of seeing one of Hitchcock’s great films, a master’s masterpiece.

Unfortunately, the third film, Bonnie and Clyde, did not air in time to be included in this week’s paper.

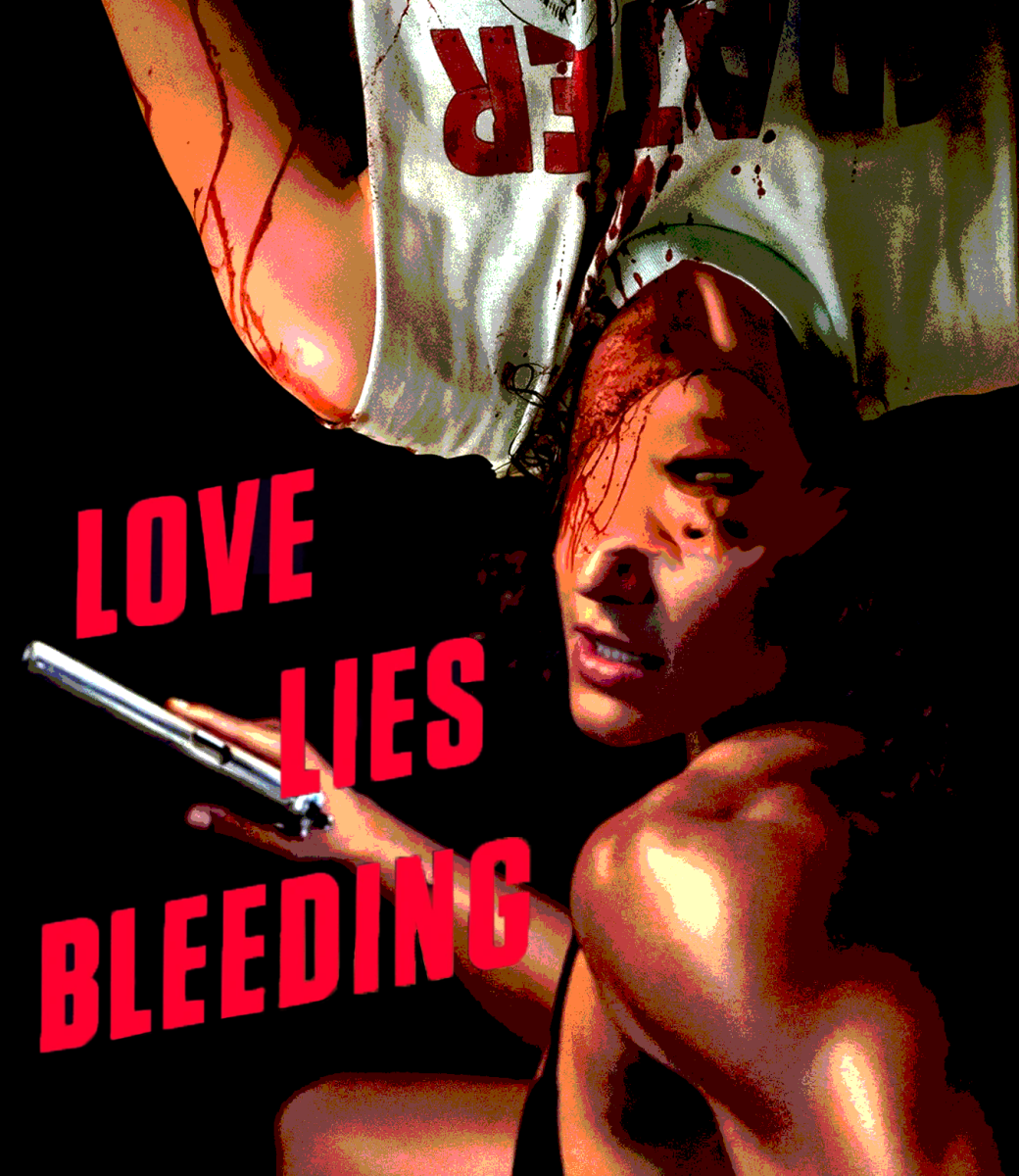

These films are works that contribute to the study of the cultural mainstay that is the blonde. According to Catharina Manchanda, Ph.D., who curated the “Beauty and the Blonde” exhibit and wrote literature accompanying the exhibit, the blonde emerged as a titan of pop culture in the 1950s. Before this period, blonde hair, especially dyed-blonde hair, was the domain of actresses, vaudeville and burlesque stars.

Manchanda said that the blonde was associated with a “frank sexuality.” She writes that Monroe’s rise to fame did not domesticate the blonde as much as it “made a sexual rendering of the blonde acceptable.”

Interestingly, in the times of the Roman empire, blonde wigs were the mark of a prostitute, but eventually became a trend among the wealthy.

The works of art in “Beauty and the Blonde” are reactions to this sexualization by artists. The appearance of commercially available blonde hair dye allowed more women to embrace their inner blonde. By the ’60s, artists understood that “hair dye [was] artifice embraced by the mainstream . It became something else,” said Manchanda.

It became two stereotypes: on one hand, there was the Monroe-like blonde vixen; on the other, the domestic beauty and the idealized wife and mother featured in advertisements for kitchen appliances and the like.

While many artists with pieces in the exhibit are well-known-there is an Andy Warhol film as well as a comic strip from Roy Lichtenstein-there are many artists outside of pop culture who have insightful critiques of the field. In the ’70s, Lynn Hershman Leeson, who was also featured, adopted a blonde alter-ego, Roberta Breitmore, who had her own apartment and driver’s license, went on dates and attended therapy sessions. Her attempt to deconstruct the blonde identity by seeing how the other half lives is intriguing and a highlight of the collection.

The best way to understand this area of art is to visit the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum (One Bookings Drive, St. Louis, MO 63130) and see the exhibit itself while it is on display until Jan. 28. Entrance to the exhibit is free, and more information can be found on the museum’s website, kemperartmuseum.wustl.edu.