Students, faculty and community members gathered on Sept. 10 to celebrate new public artwork that honors Mill Creek Valley, a mostly Black neighborhood that was demolished by city officials in the 1950s.

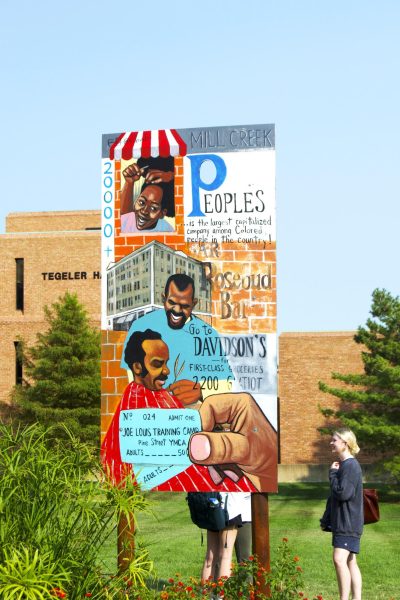

St. Louis-based artist Cbabi Bayoc created four panels, each depicting an aspect of life in the Mill Creek community. The painted panels are installed around a university fountain on the intersection of Grand and Lindell Boulevards, which was once an entrance to Mill Creek.

“I wanted to make sure that folks knew that there was a sports community here. Of course, there was a church community, very strong business-minded individuals. And then, with most neighborhoods in this country, we always have culture and music,” Bayoc said.

Prior to its destruction, Mill Creek was a vibrant neighborhood that housed approximately 20,000 people and had ties to influential figures like Josephine Baker, Maya Angelou and Louis Armstrong.

The community was destroyed in the name of “slum clearance” 64 years ago, in order to make space for U.S. Highway 40 and a variety of other development projects that never came to fruition. In the mid-20th century, Saint Louis University (SLU) bought up much of the land that once was part of Mill Creek, contributing to the erasure of the neighborhood.

SLU president Fred Pestello spoke at the event and described the aim of the artwork and its conection to the university.

“Through this art today, we celebrate what was once here on the property we stand. We celebrate what was once this thriving community. We celebrate this land that is now a part of Saint Louis University through remembering its history and the people who were here, the community that was here,” Pestello said.

Christopher Tinson, the chair of the African American Studies Department, helped coordinate the celebratory event. Tinson believes that SLU has an obligation to build a relationship with the largely African American community in St. Louis

“Mill Creek Valley is really about the 20th century and the kind of marginalization [and] deterioration that happens to Black communities in modern American cities,” Tinson said. “And then there’s this longer history that stretches back to the 19th century, which unfortunately involves African-descended people that were enslaved by the university.”

The art installation recognizes that SLU’s disparagement of the African American community did not end with their enslavement of Black Americans but continued with the displacement of the Mill Creek community.

Vivian Gibson, a former Mill Creek resident who published a memoir in 2020 about growing up in Mill Creek titled, “The Last Children of Mill Creek,” expressed that while the installation is a first step, it should not be the end of SLU’s effort to reconcile its role in the mistreatment of African Americans.

“This is a temporary installation. It can go away in a year or two, and we need something more substantial, something long-lasting, to commemorate this community and their contributions,” said Gibson.

Cathleen Fleck is the chair of the Visual and Performing Arts Department. She was one of the organizers for the event, and a part of the committee that chose Bayoc as the artist to construct an installation honoring the Mill Creek community. Fleck is also a historian and believes that art can help represent the past.

“I think if we bring art down to the human level, it can make us able to have conversations and to talk about what are some difficult things, maybe in our pasts and ways to make things better for our future,” Fleck said.

Much of St. Louis’ history with segregation is unknown to its residents, with many students likely never having heard of Mill Creek prior to this installation. Gibson said that is why it is so important to recognize the forgotten community.

“The community is essentially erased,” Gibson said. “We’re standing in Mill Creek right now, and you’ve never heard of it, and people much older than you’ve never heard of it, so this effort to bring back that memory is very important to me.”

The art installation was commissioned by the St. Louis Chamber of Commerce and supported by a grant from the Regional Arts Commission of St. Louis. Behind each panel is a message from Bayoc to its viewers, giving context to the artwork displayed on the front. Fleck spoke on how she hoped to highlight the people of Mill Creek through the art.

“They want to be remembered as, just like families, people, businesses, they had lives,” Fleck said. “They were, you know, active in their church, active in their communities, that they were people. So that, to me, was just, well, what can art do? It can help to do that.”

Gibson’s hope is that the art renews community interest in the once-flourishing neighborhood.

“I think art is the unifier, you don’t need me to be able to interpret the stories on these panels, and they can provide an opportunity for you to question, to wonder about what happened, how it happened, and how, when you’re in charge, you won’t let that thing happen again,” Gibson said.

Tinson and Fleck said they intend to pursue further restorative efforts at SLU, beyond this artwork.

“We have an obligation to make these past histories accessible to students, accessible to younger generations of people who didn’t experience them, and also help them understand that we don’t want to repeat the struggles of the past,” Tinson said.

Correction: Kathleen Fleck is the chair of the Visual and Preforming Arts department. A previous version of this article listed an incorrect title.

Robert Hughes • Sep 26, 2024 at 9:05 am

Dr. Fleck is a Professor of Art History and Chair of the Department of Visual and Performing Arts. Sara Rae Womack is the Coordinator in VPA.

Zekhra Gafurova • Sep 26, 2024 at 1:26 pm

Thank you for reading this article! We made the correction to Dr. Fleck’s title.