“Kid-Simple,” which opened Friday, April 18, at Saint Louis University Theatre, is a dizzying array of a lot of things, but mostly sight and sound.

These two elements become as vital to the story as the actors themselves. Subtitled “A Radio Play In The Flesh,” the comedy from Jordan Harrison is told in a fairy tale form from the recollection of the narrator, senior Paris McCarthy, sitting in a cushioned armchair on a platform high above the stage.

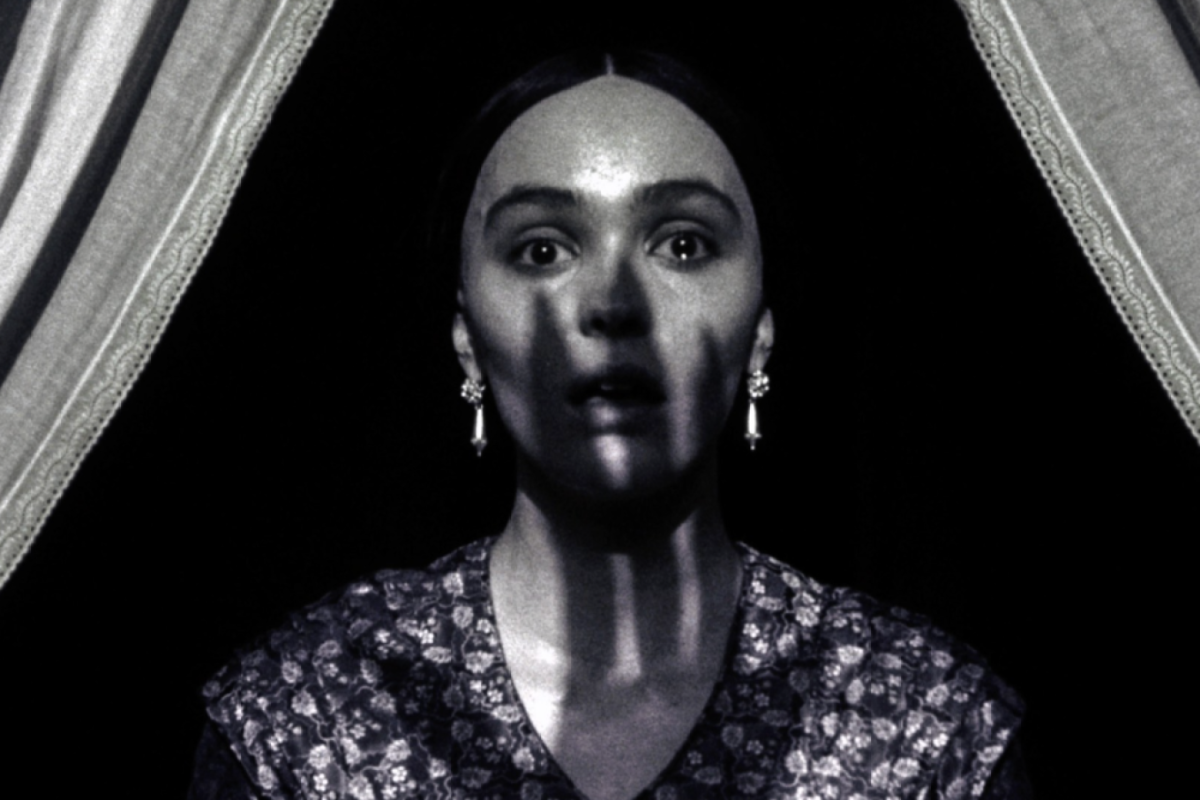

Moll (senior Katie Consamus), an adolescent Einstein who passes the time inventing things and listening to the exploits of her parents Mr. Wachtel (senior Dylan Duke) and Ms. Kendrick (senior Jennifer Stewart) on the family radio while they sit idly by, admiring their precocious young child, oblivious to her foibles.

Moll invents what she calls “The Third Ear,” a device designed to detect sounds unheard by the human ear-sounds like toenails growing on a field mouse or the distinct sound of a liar’s breath. Like most worthwhile inventions, her invention creates quite a stir, but for a reason that’s unclear.

Nevertheless, Moll is confronted by the shape-shifting Mercenary (senior Billy Kelly), master of all disguises, who desires the machine for his mysterious friends of the dark (Duke and Stewart), who want the power of hearing sounds no one can hear. Suffering from the raging hormones of pubescence, Moll falls for one of the Mercenary’s ingenious disguises-the zonked-out surfer Garth-and proceeds to unknowingly relinquish “The Third Ear” to her surfer boy toy.

Upon discovering that Garth is a fake and that her device has been stolen, Moll enlists the help of her virgin pal, Oliver (freshman James Canfield), to assist in retrieving the device and saving sound from imminent chaos. As a virgin, the stereotypical nerd Oliver possesses the ability to lure evil from hiding-or so the legend goes. Sexual innuendoes and vulgar poses ensue.

All these happenings don’t lead to much, and the plot suffers from sheer overexertion when subtlety is called for. “Kid-Simple” is convoluted by its own strangeness, eliminating any relationship between audience and actor, likely because of the complexity of the plot.

“I read over the script many, many times,” Canfield said. “It’s a very far-out play, and you can’t understand it from just reading it once . I had to do a lot of homework, investigating references that had been made in the play.”

Harrison’s ability as a writer is never in doubt, but his insistence on overstuffing the play with unnecessary gags, fanciful dialogue and references to pop culture seem forced.

That’s not to say the actors’ performances are sub-par; quite the contrary.

Consamus plays Moll perfectly, capturing that teenage angst and aggression that parents will recognize too well. Duke and Stewart are typically great in any role, although the roles they’re given simply keep the plot afloat. Canfield plays Oliver with a delicate quirkiness and nasal tone that give Moll someone off of whom to bounce her craziness. Kelly, the actor with the most roles in “Kid-Simple,” seemed to be enjoying himself immensely, despite the lunacy of his characters.

“We’re all having a really good time,” Consamus said. “We all worked really hard for this, more than usual, because it was such an ensemble-oriented piece.”

Also essential to the plot is The Foley Artist (junior Domenic Laury), who sits onstage within a large metal contraption where all sorts of sound mechanisms lie at his disposal.

At every turn during Moll and Oliver’s journey, The Foley Artist is ready to render the perfect inaudible sound to capture the moment. In case the audience fails to pinpoint a particular sound, a description of each is conveniently projected onto a wooden board above center stage: “the sound of an uncertain heartbeat” or an “unpromising mechanical whirl.”

“Kid-Simple” is an ambitious and tiresome production.

It’s surprising that the company chose such a complex and confusing one after the simplicity of “You’re A Good Man, Charlie Brown,” which was as entertaining as musicals get. “Kid-Simple” takes a lot more work, but the payoff proves minimal, and, sadly, the strong performances throughout can’t solidify a weak plot.

In the program for “Kid-Simple,” director Tom Martin wrote: “I was going to write something profound and resonant that would illuminate your path through Jordan Harrison’s clever labyrinth of a play. Then I decided against it.”

Harrison’s play may be a “clever labyrinth,” but no light is bright enough to guide us through this confusing mess of a story, which even the play’s director seems to admit.