It’s been about a year since the financial crisis hit Wall Street and various corporations across America, and about a year since the corporate giants were granted an enormous $700 billion bailout.

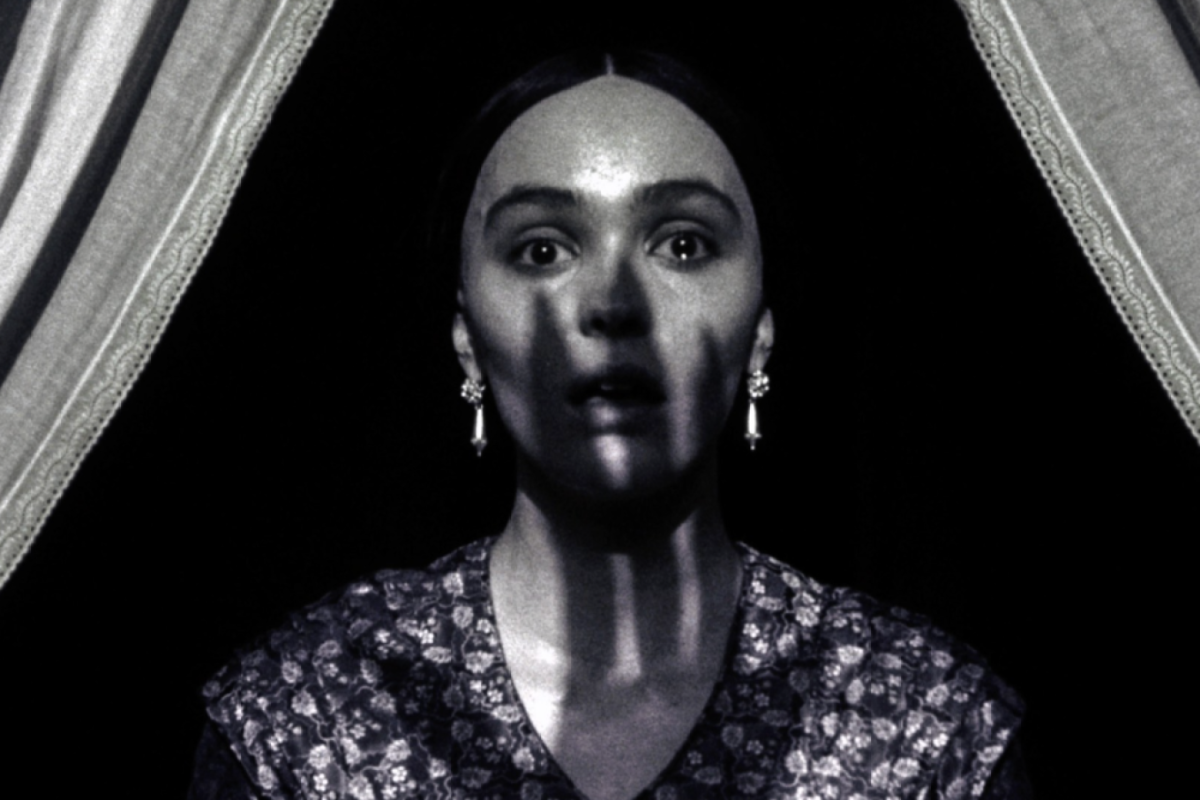

Documentary filmmaker and notorious gadfly Michael Moore (whose other works include Bowling for Columbine, Fahrenheit 9/11 and his most recent effort, Sicko) has put together his latest work, Capitalism: A Love Story (Overture Films), this time targeting big business and America’s capitalist society.

If there is one thing Michael Moore is good at, it’s riling up an audience’s emotions. Here, he is at his best (or worst, depending on who you’re asking). Just like with Sicko,

Moore makes a film that is so broad and covers an area that affects so many Americans that it’s hard to disagree with him, a fact that isn’t the case with films such as Fahrenheit 9/11, in which he decisively split his audiences. Considering that one percent of the nation has more wealth than the bottom 95 percent combined, a fact Moore reminds viewers of in Capitalism, this documentary appeals to the broad lower percentile.

Once again, Moore resorts to clever wordplay, trotting out the most extreme cases to support his arguments, public stunts, metaphors, and, of course, humor and sympathy to make his points known and effective.

Moore compares America to the Roman Empire by juxtaposing the two; he goes to headquarters of various big businesses in New York, attempting to make citizens’ arrests of their CEOs, and he shows various people who have had their lives ruined by the greed of others.

More often that not, his tactics, while not presenting both sides of the argument, work fairly well at accomplishing what he is trying to do. However, there are times when Moore hurts his own case by going too far, such as when he shows children crying about their parents who died, a manipulative move that damages a point otherwise well presented. Luckily, Moore doesn’t fall into this habit too often, which keeps him more informative than exploitative.

In all honesty, Moore doesn’t need to lay it on thick in most of the cases he presents; the ugly truth is enough to make most people want to punch a few CEOs and their government agents.

Seeing hard-working Americans getting their homes taken, not making enough to feed their families and being fired with no severance pay or notice doesn’t need to be exaggerated. Capitalism is a truly difficult movie to watch, inciting an equal amount of laughter and tears.

When the dust has settled and Moore has finished making his case, audiences are left rather downtrodden, but hopeful.

The American people have more power than they think, and future generations need to take the lessons of the past three decades to heart. Indeed, the nation FDR envisioned could come to fruition sooner or later, and recent events make it seem like the general population is headed in that direction. Even Moore’s fiercest detractors can’t deny that.

When reviewing a Michael Moore film, it’s impossible not to bring one’s own political viewpoint into the equation.

So much of what he does is tied to his views, and a viewer predisposed to harshly disagreeing with Moore might not take much from this film.

But for those open to his message or those who come from a similar perspective, Capitalism is a must-see.