Hysteria Sparks Takei’s Activism

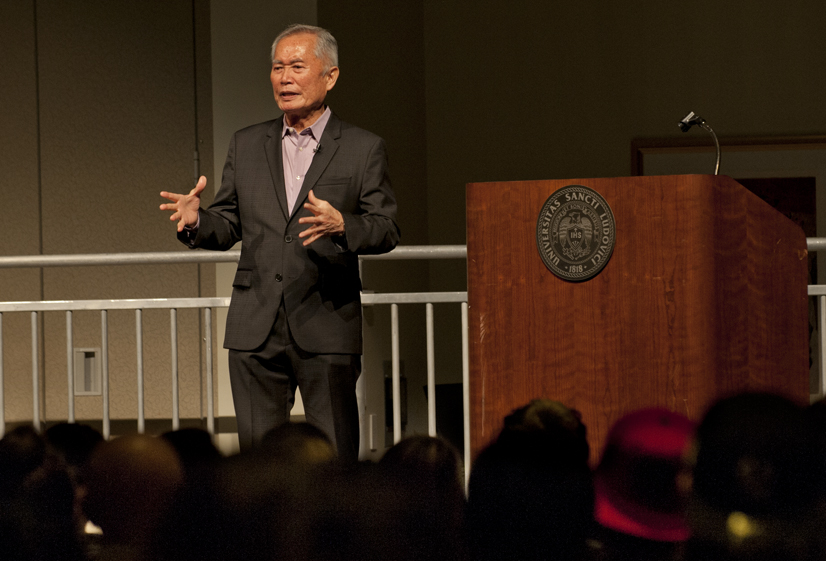

George Takei visited Saint Louis University and spoke to the SLU community about his life as an actor, activist, LGBTQ+ person, author, and Japanese-American.

Amid hysteria after the attack on Pearl Harbor rose a resilience among Japanese-American families — The Takei family was no different. Describing his battlefield behind barbed-wire fences, American actor, director, author and activist George Takei spoke to Saint Louis University students on Tuesday, October 10 in the Wool Ballroom about his experience living in an internment camp and the role it played in shaping his political activism and acting career.

Takei started with a comparison between the high of traveling up the Gateway Arch recently, sun theoretically miles away but appearing in fingertips’ grasp, and the darkness he encountered as a young Japanese-American boy after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. Because of the hysteria, Takei and his family were imprisoned in an internment camp under Executive Order 9066. No charges were pressed to cause the round-up.

From a two-bedroom home in Los Angeles, Takei and his family relocated to a horse stall until the completion of the camp’s construction. Once transitioned to internment camp Rohwer located in Arkansas, Takei described the machine guns and barbed-wire fences surrounding him. “I remember the search light that followed me when I made the night runs from my barrack to the tree, but five-year-old me thought it was nice that they lit the way for me to pee,” he said. “I was a young child and very innocent.”

Years after WWII ended and Japanese-Americans were released, Takei read history books in search of his experience in Rohwer. There was nothing.

“I couldn’t reconcile that all men were created equal, and we had an inalienable right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness for what I knew to be my childhood in imprisonment,” Takei said. As a result, he started questioning his “normal” upbringing as abnormal.

Amidst Takei’s questioning, his father explained that in a democracy, one does not give up. “What is needed for a people’s democracy is people who challenge those ideals and actively participate in the process,” Takei said. “American democracy requires people to take these ideals to heart and give all of themselves to make that democracy work.”

Takei and his father drove to an Adlai Stevenson campaign in 1952, and Stevenson lost the presidential nomination. He ran again without success. “I saw him working with other passionate people, and I understood what American democracy [had] to be,” Takei said.

From that experience, Takei became active in political campaigns for the governor of California, for the U.S. Senate from California, and for the mayor of Los Angeles. He also participated in social justice campaigns: school rights movements and musicals “Fly Blackbird!” and the more-recent “Allegiance.”

During the Vietnam War, Takei pursued an acting career. He became involved in the Entertainment Industry for Peace and Justice, working alongside Jane Fonda and Donald Sutherland. “I was active in so many social justice and political campaigns, but the one issue that was closest to me, that was organic to me, was that I was silent,” Takei said.

At 10 years old, Takei explained that he realized he was different in more ways than his Japanese descent. “When you’re a teenager, you have this great need to fit in, and particularly because we were so ostracized,” he said.

When Takei’s friends dated, he too dated his female friends to fulfill the status quo. “When I started pursuing an acting career, I knew I couldn’t let that secret out because I had enough challenges as an Asian-American,” he said. “If they knew I was gay, I would never be able to have an acting career, and I passionately wanted my acting career.”

Takei photographed with his female friends, but he also discovered gay bars where he could let his guard down. “That place was like an oasis — I could relax, meet people like me, and enjoy a bottle of beer while having a couple of conversations,” he said.

However, Takei worried because police raided gay bars, and often fingerprinted, photographed, and took down people’s information. “If any of that got out, it would be devastating because people would lose their jobs,” he said. “Exposing people was the same mentality [of the internment camp] — criminalizing innocent people.”

Although Takei wanted to be vocal about his sexuality as he was in the civil rights movement, he did not want to become a no-name actor.

In 2005, California passed marriage equality through the state legislature. But, the bill needed Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger’s signature. He vetoed.

“I was boiling, and by this time, I found Brad [Altman], the person who I wanted to spend the rest of my life with,” Takei said. “I had an obligation as a gay citizen, and I spoke to the press for the first time as a gay man and blasted Arnold Schwarzenegger.”

Since the veto, Takei actively participated in LGBTQ+ campaigns. In 2008, he and Altman married after the California Supreme Court ruled marriage equality the law of the state.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Saint Louis University. Your contribution will help us cover our annual website hosting costs.

Staunch entered SLU as a Biomedical Engineering major on a Pre-med track, with the intention of continuing her studies in medical school. After a year and a half at SLU, she realized she missed the balance of the arts with sciences as she was previously an editor in her high school yearbook committee.

"Working for UNews, whether it was as Associate News Editor, Managing Editor, or Editor-in-Chief, has taught me the value of working on tight deadlines and how to adequately adapt to certain unexpected situations. The field of Journalism is incredibly fast paced - but that is why I love it so much," Staunch said. "There is always something new occurring, and you would not be able to effectively complete your job unless you had the support of your other editors and staff."

Though paradoxical in nature, she switched her major to Communication. She wants to incorporate both her analytical and creative sides to report on medical topics. Her dream job: to write for Discover Magazine.

When Staunch is not in the newsroom, she is captaining the women’s Ultimate Frisbee team at SLU. She began playing her freshman year and enjoys it as an outlet.