It’s almost game day at Saint Louis University again. Soon, the ubiquitous yard signs will pop up on West Pine Boulevard; students, alumni and fans alike will flock to Chaifetz Arena to watch 15 of their favorite student-athletes throw a ball around.

But don’t forget about the 300 other student-athletes on campus. And just about every one of them will go pro in something other than sports, as the NCAA so kindly reminds viewers during every multi-million dollar television broadcast. Don’t tell that to the student-athletes though. In a 2010 NCAA survey, 76 percent of men’s basketball players and 37 percent of athletes in all other sports felt they were at least “somewhat likely” to go pro in their respective sport.

If that average NBA career of 4.7 years doesn’t pan out though, at least they have that valuable Saint Louis University degree to fall back on, right? The average basketball player at Division I private institutions comes to school with an SAT score about 200 points lower than that of the general student body, according to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. The wealth of tutors and other academic assistance offered to athletes intends to keep them up to par. Student-athletes graduate at a slightly higher rate than their counterparts, albeit with lower GPAs.

So after their sneakers set foot on SLU’s lawn, how do athletes fit in with the rest of the student body? Beyond the stereotype that they “ride motor scooters and are taller than me,” as a junior sociology major put it, how does an athlete’s college experience differ from that of a “normal” student?

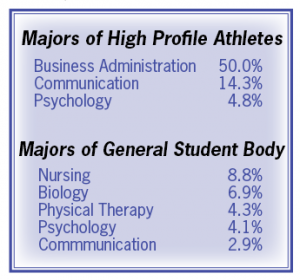

Everyone has to choose a major when they arrive on campus. For the general student body, the most popular picks are nursing, biology and physical therapy. For the athletes in “high profile” sports (defined as baseball, basketball, football and hockey), a full 50 percent choose business administration, followed by 14 percent in communication.

There are many theories for this difference, some real and some contrived.

“A common stereotype I’ve heard thrown around campus is that athletes are communication or business majors, [the] ‘blow-off majors’ in certain regards,” a junior education major said. “It’s quite understandable, as sports take up a lot of time.”

“For us [the business school], it’s fortunate; they’re in a top-level business school. If they are coming here for an easy ride, they’re going to get smacked around,” said Dr. Anastasios Kaburakis, a sports business professor in the John Cook School of Business. “They have lists of classes student-athletes would cluster in at Stanford; if you have it there, you’re going to have it everywhere.”

There is also a natural tendency to want to take classes that one’s peers are taking, creating a certain “athlete culture” in this case.

“There is a unique sense of community and connection among student-athletes that can’t really be understood from the outside,” Brooke Urzendowski, a sophomore tennis player, said.

This athlete culture includes many things. First, according to the earlier mentioned NCAA survey, 91 percent of athletes report feeling a strong connection to campus, much more than any other student subset. However, a 1996 study also shows that “athletes report having grown less as people in college and having spent limited time at cultural events or pursuing new interests.”

“I do not have a study-first mentality per se,” said Nishaad Balachandran, a junior tennis player. “I have always maintained [that] education is important, but not as important as my tennis.”

While many athletes have this “single-minded” focus, as Balachandran phrased it, they may be missing out on other things while they shed sweat on the court.

“They are missing out on chances to interact with faculty, students, and enjoy other initiatives,” Kaburakis said. However, he added that, “SLU is a good example of an institution that tries to keep a good balance…you will still see athletes being involved in different things.”

In that 2010 NCAA survey, men’s basketball players reported spending two hours more on athletics than on academics during a typical week. It’s important to remember though, that SLU student-athletes “aren’t the SEC [Southeastern Conference] athletes that everyone hears about on the news,” as former basketball player Brian Conklin said.

While there is a perception that athletes miss out on many aspects of the vaunted “college life,” the vast majority have no regrets in their decision to pursue collegiate athletics.

“I don’t have any regrets as far as not being able to spend as much time on other extracurricular activities,” Urzendowski said. “The tennis team puts a great emphasis on academic achievement.”

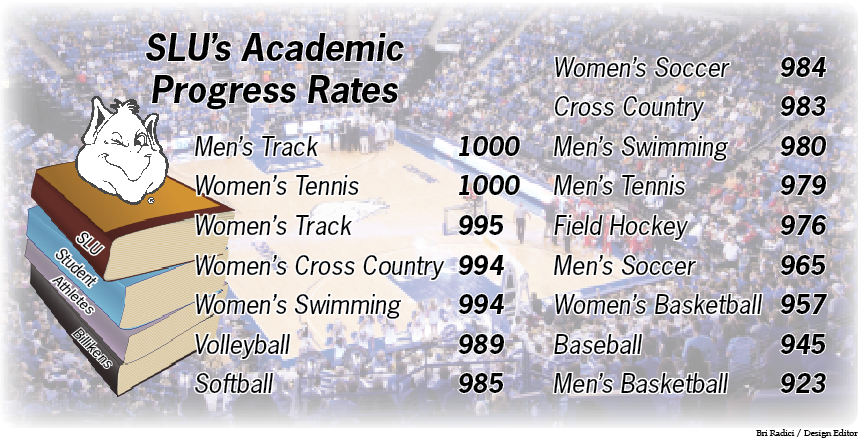

When looking at the NCAA Academic Progress Rate, an NCAA measure of athlete eligibility and retention, for different SLU athletic teams, it is easy to see truth in Urzendowksi’s claim. The women’s tennis team had a score of 1000 for the 2010-2011 season, representing a 100 percent graduation rate among its players. This compares favorably to the two lowest performers at SLU, baseball with a score of 945 and basketball with a score of 923, the latter being roughly equivalent to a 50 percent graduation rate.

In fact, after recent NCAA reforms, a four-year average score below 930 will soon confer postseason bans for the offending team.

So, what does the term student-athlete mean at Saint Louis University now? Part meme and part marketing ploy, the term was once as pristine as the dolphin pond.

Originally, intercollegiate athletics was a way for schools to espouse their mission, coaching students in the “game of life.” Somewhere along the way, amid the two-a-day practices, taxing travel schedules and multi-million dollar television contracts, athletics lost its way. Its role on campus and in the community has undoubtedly changed.

“We are like a walking image of campus,” Conklin said. Athletics provides a tangible link between the campus and the outside community or alumni. A much stronger connection is felt to the uniformed hero commanding the court than the quirky intellectual or virtuoso violinist.

The very term student-athlete is meant to perpetuate the myth that the athletes in high-profile sports are still students first, that athletics is secondary to academics—something akin to being a student government senator, a member of the pep band and yes, even an editor for the school newspaper.

Division I athletes report a stronger athletic self-identity than academic and attribute their college choice more to athletic considerations than academic. Unfortunately, this pattern is often reflected in schools’ own behavior.

“That is definitely reasonable and understandable,” Kaburakis said. “The overall environment that has been created in the past 100 plus years is something innate in American culture.” Athletics call upon humans’ passions in ways that even the most spirited of academic debates cannot fathom.

So, if it looks like an athlete, spends more time on athletics and identifies as an athlete, why is there an insistence upon calling it a student-athlete?

For many athletes in low-profile sports like Urzendowski, it remains the truth. Even Conklin, a star on last year’s Billiken squad, felt this way, earning an MBA in just four years.

“We really enjoy the same chance at a free meal that every other student is excited for. You just have to interact with the student body and show that you struggle with professors and homework too,” Conklin said.

“You get the best of both worlds, I get both in my classes too,” Dr. Kaburakis said.

These few remaining student-athletes are increasingly in the minority though. Not only do many feel they are athletes first; increasingly, schools and society treat them this way. From a young age, students are indoctrinated with the notion that athletic pursuits are more valued than intellectual endeavors. And nowhere is this dichotomy more entrenched than in the country’s universities, the supposed harbingers of intellectual progressivism.

Now, it’s off to Chaifetz Arena for tipoff. It is game day—time to watch everyone’s favorite athlete-students.