The St. Louis metropolitan region saw extreme rainfall this month. In a matter of just 24 hours from Nov. 4 to 5, 7.64 inches of rain fell in the region, breaking a previous record of 6.9 inches set in 1915.

The flooding killed two people in Missouri and many residents reported flooding in their homes.

The historic rain came amid a four-week-long drought in Missouri. From the end of September, when the region received rains from Hurricane Helene, to the start of November, the state was one of several in the Midwest to fall victim to drought.

As droughts stretch on in many parts of the world, the chance of rainfall may seem like a welcome relief. However, the gift of rain can quickly turn into a danger, especially when the rains come too heavily or too suddenly.

This weather event had the National Weather Service (NWS) post severe weather and flood warnings for the greater St. Louis region.

The biggest threat in the St. Louis metro area was flash flooding, which occurs when the ground is so unsaturated that it cannot handle the high amounts of rain.

“Excessively dry ground and high amounts of rainfall can actually work against each other,” said meteorology graduate student Lizzie Bannon.

When precipitation cannot be absorbed, it becomes groundwater, which usually travels downhill, leading to flooding.

Flash flooding can be dangerous due to man-made infrastructure as well.

“Metro areas are prone to flooding because of the amount of surfaces that cannot contain groundwater, like roads and parking lots,” Bannon said.

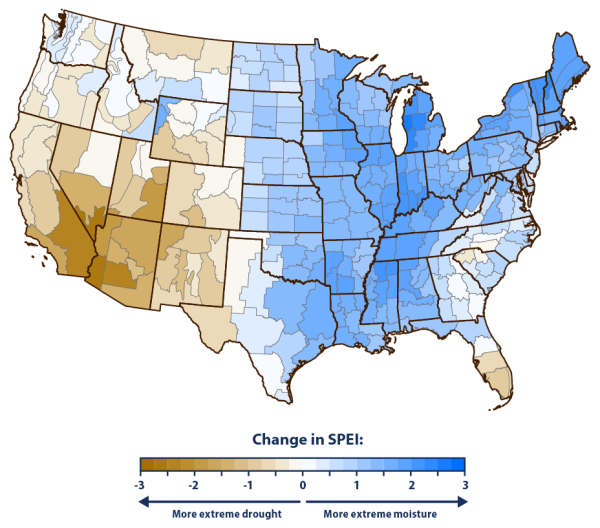

(Graphic courtesy of United States Environmental Protection Agency. June 27, 2024)

Not every major city is prone to flooding, but the geographical location of St. Louis does not help its case.

St. Louis is located on the outskirts of the Ozark Mountains, making the region hilly. The city is also in the cross-section of two major river basins: the Mississippi and the Missouri. The metropolitan area is riddled with other rivers and creeks that contribute to additional flooding.

“With the hilly terrain, the downhill momentum is what causes the flash flood,” said Brady Wurmnest, a junior studying meteorology. “The racing waters can pick up debris along the way, which adds additional danger.”

It is important to know how to stay safe during flood warnings. If you come across a flooded road, do not drive through.

“The saying ‘turn around, don’t drown,’ is more than just a rhyme,” Bannon said. “It only takes a few inches of running water to float a vehicle.”

This is not the first time that St. Louis has had extreme floods similar to the ones on Nov. 4 and 5. Climate change can make extreme drought and extreme floods more frequent and more dramatic.

“In Missouri, we are overall seeing an increase in flood frequency and flood magnitude,” said Carly Finegan-Dronchi, a doctoral student studying geoscience.

Finegan-Dronchi said there is a pattern where heavy rainfall is followed by a period of dryness; but once it rains again, it will be consistent for two to three days.

“Thinking about this fall, the month of October was very dry overall, and now we can’t seem to escape the rain,” Finegan-Dronchi said.

Scientists say climate change has contributed to an overall increase in atmospheric moisture, leading to heavier rainfall in some regions, including the Midwest.

Global warming brings warmer temperatures, which means that the atmosphere can hold more moisture, contributing to intense rainfalls when conditions are right.

Due to a projected weak La Niña, a wind pattern that occurs in the Pacific Ocean, St. Louis will see some cooler temperatures mixed with a below average chance of winter precipitation for the rest of the year and into early 2025.