Nearly three years since Russia’s full-scale invasion, war has become an inescapable backdrop to daily life in Ukraine. For Ukrainian citizens, the initial shock of the February 2022 invasion has long since given way to a brutal, exhausting routine of air raids, power outages and uncertainty.

An overnight Russian drone strike on Dec. 2 hit critical infrastructure and left parts of Rivne and Ternopil without power. A drone struck a residential apartment building, and one person died with others receiving injuries.

The next day, life continues. On a cold December morning in Ternopil, Ukraine, a school bell rings just minutes after an air raid siren finishes blaring through the city. Students file into classrooms clutching their backpacks, while teachers ensure their lesson plans are accessible offline, just in case the power cuts out.

Amid the destruction, air raid sirens and power outages, people have adapted, finding ways to work, study and celebrate even as their cities are bombed. These stories of resilience illuminate a truth that is both sobering and inspiring: life will never be the same again, yet life must go on.

Ternopil resident Yaryna Yasinovska is growing up with the war all around her. The 13-year-old attends school and art club, used to the constant air raids and nightly power outages.

“What else are we supposed to do? Life goes on, and we do our best,” said Yaryna’s father, Andriy Yasinovskyy.

In the distance, a bakery owner flips a “We’re Open” sign on her window, knowing a missile strike could shatter it any day. Life here is lived in fragments, yet somehow, it continues.

For many Americans, war is an abstract concept, confined to history books or fleeting headlines. But for millions of Ukrainians, it has become a relentless backdrop to ordinary life. As international focus shifts and political dynamics evolve, Ukrainians suffer, adapting to a reality where the future remains uncertain and the world’s commitment to their cause appears increasingly tenuous.

In a significant geopolitical shift, the United States, under President Donald Trump, has altered its stance on the war, shifting support away from Ukraine and breaking away from years of American sanctions on Russia.

Recent actions include voting alongside Russia against a United Nations General Assembly resolution condemning Russia’s actions in Ukraine and engaging in bilateral negotiations with Russia, sidelining European allies. These developments have left many Ukrainians questioning whether their struggle for sovereignty remains a priority for Western powers.

For regular people in Ukraine, life has been forever altered by a war they did not ask for.

Civilians, who often have no involvement in the conflict, face disproportionate consequences such as displacement, loss of livelihood and psychological trauma. According to the United Nations, over six million Ukrainians have been displaced within the country, while another six million have sought refuge abroad. This staggering figure represents nearly 30% of Ukraine’s pre-war population, underscoring the immense human toll of the conflict. Children account for nearly half of these refugees, with many growing up in unfamiliar environments or without access to proper education.

Women and children are particularly vulnerable to the war’s ripple effects. A report by the World Health Organization highlights how maternal and child health services have been disrupted in conflict zones, leaving many without critical care.

Psychological trauma is also widespread, with over 80% of displaced Ukrainians reporting symptoms of anxiety or depression, as documented by a recent survey from the International Organization for Migration.

In communities directly affected by the war, civilians are finding ways to survive despite immense challenges. Many neighborhoods have organized volunteer networks to distribute food, clothing and medical supplies. Local schools have set up underground classrooms to continue teaching children during air raids. Despite these efforts, the long-term effects of the war, including economic devastation and intergenerational trauma, will be felt for decades to come.

Their lives may never return to what they once were, but they press on in the face of relentless adversity. Because for them, there is no other choice.

Olena Hudz, a journalist who now spends her days as a war hospital volunteer, described the profound toll the war has taken on ordinary Ukrainians.

“Basic everyday necessities have been stripped away,” Hudz said. “No electricity for eight hours is common. Outside of the rapes, stealing — everything the Russian soldiers are doing — how do we explain this?”

Although she knew war was inevitable, she never imagined it would be this devastating.

“We never sleep,” Hudz adds, explaining how Ukrainians rely on Telegram channels for updates on incoming threats like rockets, ballistic missiles and Shahed drones. The warning systems, she notes, are loud and located close enough to be effective, but they have become a constant, relentless backdrop to daily life.

Despite the danger, Hudz and her neighbors no longer go to shelters when the sirens sound.

“We don’t have good bomb shelters around here,” Hudz said. Instead, they sleep in hallways, adapting to the circumstances each new day brings.

“It’s terrifying that we are used to it, that we have adapted,” Hudz said. Like many Ukrainian parents, she wrestles with the choices she has made for her family. “Of course, I ask myself all the time if this was the right choice, if I should have stayed and kept my kids here to be kids of war.”

Yet, she continues to face each day with resilience, embodying the unyielding spirit of those determined to endure.

In Ukraine, civilians like Hudz have organized resistance efforts, fought to defend their communities and supported each other despite immense challenges. This kind of civic resistance underscores the dual role civilians play as both victims and active participants in shaping their futures.

There have been large changes in Ukraine’s social fabric. Families gather in candlelit rooms during blackouts, finding solace in shared moments. These acts of normalcy are not merely survival tactics — they are declarations of humanity.

Ternopil Yasinovskyy lives in Ternopil, Ukraine, with his wife and two children. At the end of 2021, they bought a house out in the country, hoping to finish renovations on it within the year and move in. The war has stalled those efforts almost completely, Yasinovskyy explained, with many contractors enlisting, leaving the country, or taking on significantly fewer jobs because of a worker shortage and how stretched-thin resources are.

In addition to the struggle to find workers, the financial burden of the war weighs heavily on families like the Yasinovskyys. A significant portion of many Ukrainians’ income goes toward donations, usually not to large humanitarian funds but directly to volunteers they know.

Fundraising efforts for drones, Starlinks, charging stations, vehicles and repairs are constant, and often, the people collecting are raising money for brigades where their own relatives serve. Financial contributions are a way to protect loved ones and support those on the front lines.

Yasinovskyy showed The University News pictures of the house, as well as the renovation plans, explaining how they are trying to be patient even though the process has been frustrating.

“We had planned everything out for that house, had a complete design mock-up, knew where we wanted to put the plants in the living room. But of course, none of that happened. Two years later, the house still had no stairs connecting the main and second floors,” Yasinovskyy said.

This stagnation is happening all over the country. Businesses are being forced to close. Volunteer efforts that boomed in support in 2022 are finding it hard to garner support. Fundraising is getting harder and harder, whether overseas or from their own countrymen.

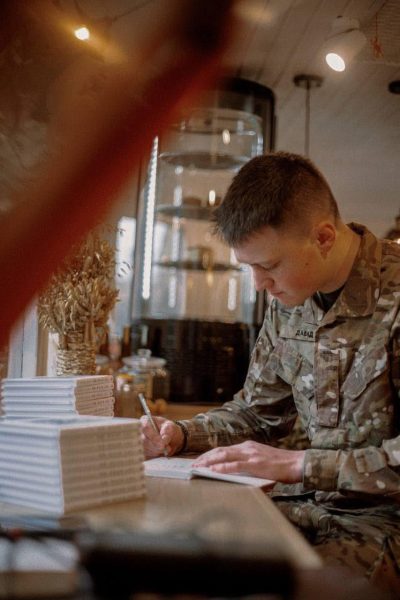

In February 2022, there were long lines at enlistment offices as the number of people willing to join the army exceeded the military’s needs, but those numbers have fallen, with many casualties in the last three years and a general large drop in passion for the war effort. Throughout the last three years, the military has been carrying out constant mobilization measures to replace those who have died or been seriously wounded.

Artur Dron, a young Ukrainian poet who joined the front lines in 2022, said it is sad to see global attention diminish and support wane around the war, even as the situation worsens.

“I always want to emphasize that abroad, the saturation of information about the war in Ukraine is becoming less and less, but in our country, the war is a daily reality. An American in 2022 heard much more about the war than now, so it may seem to him that it is winding down and ending. But it is not so. Nothing has ended, people die in our country all the same,” Dron said.

The diminishing media coverage frustrates many Ukrainians, who fear that their suffering will be forgotten. Dron’s poetry captures the heartbreak of living through a war that the world seems eager to move past, even as bombs continue to fall.

“To me, describing pain should never be the goal. The goal should be to outline light—something that stands in contrast to war’s horrors, which will inevitably be present in the poem anyway,” Dron said.

He writes poetry from the front lines, but his poetry is “not about war.” The poems describe events and people he has encountered. Dron’s book, “We Were Here,” was originally published in Ukraine in 2023, and an official English version is available for preorder on Amazon.

“[Poetry] can tell the readers a little more about the purely human aspects of our experiences. Without comments about any political, global things,” Dron said.

People’s motivation lies in community, with young people who are vocal about their beliefs and willing to fight for them, like Dron. In the efforts of local volunteers like Hudz, working to rally their communities and get support for wounded soldiers who often feel forgotten. In children like Yaryna, who go to school and art class despite the daily bomb threats, knowing that soldiers are fighting to protect their rights.

Hudz said that it is hard to rely on politicians or the outside world when you live in a country that has been at war for three years. Aid packages can be deferred, slowed and even revoked. Promises are not always kept, both by foreign leaders and the country’s own.

“You need to be your own hope,” Hudz said. “When everything feels hopeless, I have to believe in myself.”